Decolonizing Preston Bradley Hall

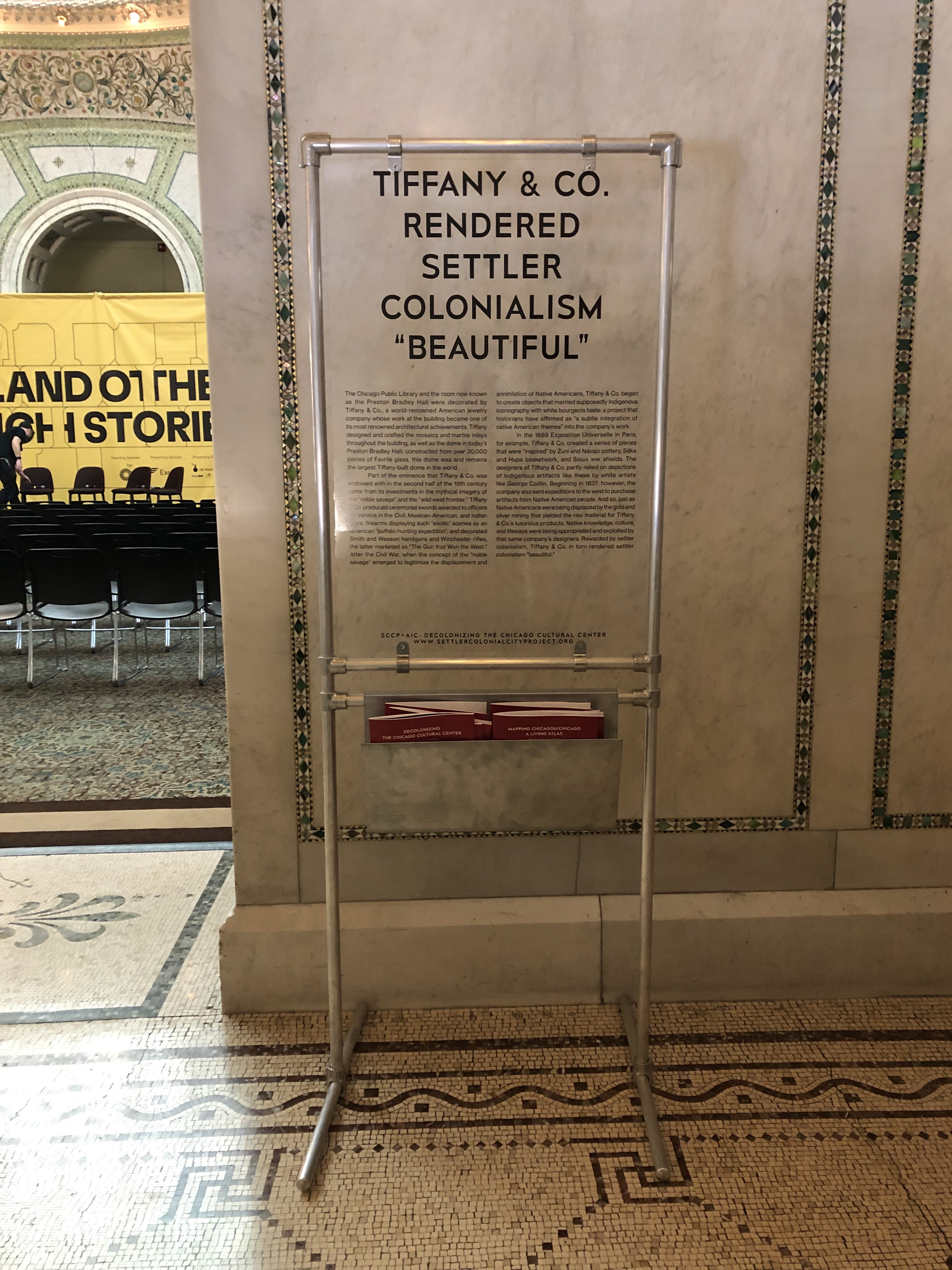

TIFFANY & CO. RENDERED SETTLER COLONIALISM “BEAUTIFUL”

SCCP 2019

At Preston Bradley Hall Foyer, Chicago Cultural Center

The Chicago Public Library and the room now known as Preston Bradley Hall were decorated by Tiffany & Co., a world-renowned American jewelry company whose work at the building became one of its most renowned architectural achievements. Tiffany designed and crafted the mosaics and marble inlays throughout the building, as well as the dome in today’s Preston Bradley Hall; constructed from over 30,000 pieces of Favrile glass, this dome was and remains the largest Tiffany-built dome in the world.

Part of the eminence that Tiffany & Co. was endowed with in the second half of the 19th century came from its investments in the mythical imagery of the “noble savage” and the “wild west frontier.” Tiffany & Co. produced ceremonial swords awarded to officers for service in the Civil, Mexican-American, and Indian Wars; firearms displaying such “exotic” scenes as an American “buffalo-hunting expedition”; and decorated Smith and Wesson handguns and Winchester rifles, the latter marketed as “The Gun that Won the West.” After the Civil War, when the concept of the “noble savage” emerged to legitimize the displacement and annihilation of Native Americans, Tiffany & Co. began to create objects that married supposedly Indigenous iconography with white bourgeois taste: a project that historians have affirmed as “a subtle integration of native American themes” into the company’s work.

In the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, for example, Tiffany & Co. created a series of pieces that were “inspired” by Zuni and Navajo pottery, Sitka and Hupa basketwork, and Sioux war shields. The designers of Tiffany & Co. partly relied on depictions of Indigenous artifacts like these by white artists like George Caitlin. Beginning in 1837, however, the company also sent expeditions to the west to purchase artifacts from Native American people. And so, just as Native Americans were being displaced by the gold and silver mining that yielded the raw material for Tiffany & Co.’s luxurious products, Native knowledge, culture, and lifeways were being appropriated and exploited by that same company’s designers. Rewarded by settler colonialism, Tiffany & Co. in turn rendered settler colonialism “beautiful.”