Press

I was particularly taken with “Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center” by the Settler Colonial City Project (SCCP), which is led by two architects, Ana María León and Andrew Herscher, in collaboration with Chicago’s American Indian Center. It comprises several signs posted throughout the Cultural Center that describe how this decked-out, Beaux Arts building — which is quite beautiful and strange in its own right — is made up of materials extracted from land stolen from indigenous peoples, not to mention built on such land and completed with labor practices that don’t live up to contemporary ethical standards, while also being frosted with decoration and messaging that romanticize indigenous peoples as “noble savages” and normalize the removal and reduction of their populations. It’s sort of the equivalent of reading the full ingredients list on the bag of Doritos you’re eating and thinking “damn these are good, but holy shit!” Or it’s like the scene in “The Shining” when the elevator doors open and an ocean of blood — the blood of slaughtered Native Americans — floods the hallway.

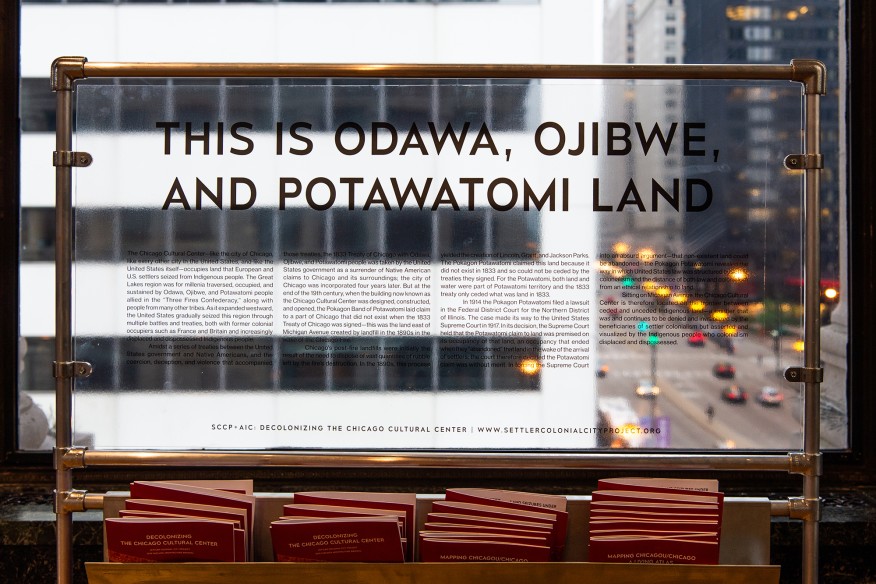

The translucent displays of “Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center” are inconspicuous, but the stories printed on these reveal an important history.

Throughout the building transparent panels featured bold headlines such as “Tiffany & Co. rendered settler colonialism ‘beautiful’’” and “This marble was quarried and assembled by exploited labor,” along with detailed texts and books to take away, forcing visitors to confront the ever-prescient architectural questions of who built our built world, on whose land, and with what resources. It was the work of the research collective Settler Colonial City Project as unobtrusive yet unavoidable didactics.

Executed in a provisional style suggestive of a guerrilla action, their Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center (2019) uses transparent plexiglass signage and vinyl text to make a series of interrogative annotations throughout the landmark building, delineating histories of genocide, land theft, and forced labor entangled in its construction. A text at the building’s northern entrance begins: this marble was quarried and assembled by exploited labor.

The overplaying of architecture’s power to solve societal issues has been a problematic trope in biennials. It’s come to a head multiple times, perhaps most recently and explosively in 2016, when the U.S. Pavilion’s Venice Biennial exhibit, “The Architectural Imagination,” which presented speculative projects for a post-bankruptcy Detroit, was occupied by Detroit Resists. The protest’s leaders insisted on architecture’s “political indifference,” and that “the U.S. Pavilion, precisely as an attempt to advocate ‘the power of architecture,’ is structurally unable to engage this catastrophe and will thereby collaborate in the ongoing destruction of the city.”

The curators of “…and other such stories”—Yesomi Umolu, Sepake Angiama, and Paulo Tavares—do not seem to believe in the power of architecture to enact political change. What’s on show at this year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial is, perhaps, the start of a different theory of change altogether.

...

The curators seem to have few illusions that architecture can change the world; indeed, the exhibits reveal how complicit architecture is, and has been, with the status quo. This comes through most clearly in Settler Colonial City Project’s contribution, a series of clear acrylic signs painted with messages like “THIS MARBLE WAS QUARRIED AND ASSEMBLED BY EXPLOITED LABOR.” The project unpacks the dark history behind the production of our buildings and cities and puts it on display. It’s perhaps not what visitors came to look at, but it’s what they’re being asked to see.

Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center is a subtle and artful reframing of the gallery spaces, which might otherwise appear to be a contextless “neutral container” for the work. Glass panels call out the exploitative history of the very materials that make up the Cultural Center, and the ways the building was used to obscure the racist history of American westward expansion. (The installation is by the American Indian Center and the Settler Colonial City Project; the panels were designed by Chicago’s Future Firm.)

“If they took the longest duration [of history], we took the shortest one,” [Eyal] Weizman notes.

The plaques are counter-phantasmagoric, in that they reveal the social character of labour in commodity production that capitalism tends to hide.

Photo Cory Dewald at Architect Magazine

Photo Cory Dewald at Architect MagazineSettler Colonial City Project’s naming project, whose simple texts, spread throughout the Cultural Center, evoke the Native American spaces that were previously in the city, and highlight the fact that some of the building's material was made with exploited labor. All you get, however, are the words. Why showing photographs or paintings of what was lost, or how the land was appropriated, would somehow have detracted from that message, I do not know.

ps. Aaron, the city IS the picture!

A signal contribution is the Settler Colonial City Project and American Indian Center’s ‘Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center’, a series of glass panels installed in various locations throughout the historic building that has been the Biennial’s primary venue since its 2015 debut. The placards bear messages about the history of the Center itself, pointing out for example that its exquisite Tiffany ceilings ‘legitimise the displacement… of Native Americans’, owing to the glass company’s appropriation of Sioux and Navajo motifs.

Part of Mapping Chicagou/Chicago: A Living Atlas by the Settler Colonial City Project, information boards identify markers of exploitation embedded into the architecture around the venue. In one hall, the words 'YOU ARE LOOKING AT UNCEDED LAND' are pasted onto the windows.

As part of their Settler Colonial City Project, professors Ana María León and Andrew Herscher have installed a series of placards in the Chicago Cultural Center's various rooms and halls. On each, they highlight glossed-over facts about the colonialism that contributed to Chicago's urban development.

...

According to Tavares, the provocative project encourages visitors to question their everyday surroundings and "excavates the many ways in which the histories of colonialism register within this very building."

... one comes away from ...and other such stories with a deepened sense of architecture's complicity, rather than it's saviour complex.

That's exemplified in Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center, a series of tightly designed, clear acrylic signs placed around the biennial venue notating acts of settler colonialism.

Created by the Settler Colonial City Project, founded by architectural historians Ana María Leon and Andrew Herscher, in collaboration with Chicago's American Indian Center, it is a physicalised hypertext of how the construction of the iconic structure was part of express crimes against Indigenous lands and people.

Architectural historians Ana María León and Andrew Herscher of the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Planning lead a research team that has partnered with AIC, the country’s oldest Native community center, to annotate both the Chicago Cultural Center and the American Indian Center complex in a way that highlights each building’s complicated and inconvenient histories.

Interview with Andrew Herscher and Ana María León for SCCP (at 43’23”). We were not asked about the BP sponsorship but you can read our take in the post for our event, “The Petro Biennial Complex.”

The project tags what is traditionally valued and reminds the viewer of its true history. Bold text printed on the windows of Yates Hall overlooking a corner of Millennium Park read: “You are looking at unceded land.” Another example, the Tiffany-built dome in Preston Bradley Hall, is admired as the largest in the world with 30,000 pieces of glass. However, León and Herscher note Tiffany & Co.’s long practice of appropriating designs from Indigenous people and acknowledge these people’s displacement.

Further reinterpretations of the building’s 1893 architecture are presented throughout by the Settler Colonial City Project and American Indian Center in "Decolonizing the Chicago Cultural Center." These interpretations are mounted on ethereal glass panels (designed by local practice Future Firm) that explore topics including the building’s displacement of native populations and the employment of exploited labor in its construction. The genius of the glass panels is that it allows the Cultural Center’s magnificent walls and ornaments to be clearly seen through the panel that describes the hidden problems with its cultural production.

The unsettling information about the Cultural Center, produced by a research group called the Settler Colonial City Project and the American Indian Center of Chicago, are just the beginning of an exhibition that revels in digging below the surface to reveal disturbing narratives.

Yet the site-wide installation, led by architectural historians Andrew Herscher and Ana María León, both of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, “annotates” the material and spatial histories that constitute this luxurious spectacle through a series of didactics strategically placed throughout the building, as well as a corresponding publication.

The project's premise is a perfect example of evolved architecture programming: celebrating beautiful buildings is a skin-deep practice; a thorough airing of problematic histories of buildings and the people who made them is greatly needed.

They have created their contribution in collaboration with the American Indian Center (AIC), the country’s first Native community center. With the AIC’s help, León and Herscher hope to demonstrate to visitors “that there is an Indigenous knowledge of and politics around land and life that opens onto very different and, we believe, sustainable and equitable futures that are crucial for us to work towards.”